Social projects

The Secret to Good Teaching

By Hanne S. Finstad, founder of Scientist Factory.

Why are some schools better than others at developing their students? Socio-economic conditions are often used as an explanation. But is it that simple? Results from two great schools in South Africa indicate that socio-economic conditions need not be the end of excellent educations.

A chaotic beginning

Melanie Smits founded the Streetlight School in the township Jeppestown in South Africa in 2016. All the students came from unstable homes. The goal was to prove that all children can learn and become good students regardless of their background. The Norwegian teacher Heidi Augestad received this challenge when hired to be the school’s first principal.

The first few weeks were chaotic, and the teachers were in shock, Augestad told Scientist Factory when we visited the school in the fall of 2019. Four years later, the students perform as well as students from high-income countries. This is the story of how they pulled it off.

Riots and poverty

Jeppestown is a township in Johannesburg characterized by poverty, crime, and social unrest. Many people live in occupied buildings without access to essential services like running water. Most of the children come from unstable homes, and the school was shut down two weeks before we arrived because of riots.

Nobody knew how to stand on line

The school welcomed 80 students aged 5-7 years old on their opening day in 2016. The faculty quickly understood that they had to create safe routines for the student’s play and learning. A slide had to be closed off for the first year because none of the children knew how to wait for their turn.

Love and reason

Augestad implemented two rules that she felt the school needed in order to progress: love and reason. The students should feel loved and appreciated. The teachers, therefore, had to practice understanding rather than judgment.

This was no easy transition. There is a strong tradition for punishment, and often corporal punishment, in South Africa. Many of the teachers had previously worked in traditional schools. The students also had to learn to reflect on their actions. Every time a child did something wrong such as punching or biting another student, the teachers helped them think through why that happened and how it affected other students.

The teachers had to support each other

The organization Responsive Classroom gave Augestad ideas for how she could create a school culture that prioritized the students’ social and emotional wellbeing. Among other things, she implemented a daily morning meeting where students and teachers could enjoy a safe start to the school day.

“I believe that inclusion and faith in all students are the most important elements of school culture. In the beginning, it was difficult to get the teachers on board with this idea. There is a long tradition for blaming mental, economic, social, cultural, and religious differences when students don’t succeed. Step by step, we were able to include all the children and adapt the pedagogical work according to the students’ needs,” Augestad explains.

The Workshop Model

They used a model called The Workshop Model in lessons. The teachers follow a set structure for each class. The lessons start with a 2-3 minute opening where the goal is to waken the students’ interest. Then they move on to a mini-lecture that goes on for about 10 minutes. The teachers use this time to explain how they are to work. The students then get 20-25 minutes to explore for themselves, where they can work on different levels adapted to their skills. The lessons end with all the students sharing and reflecting on what they have done and learned.

“The Workshop Model has an array of positive effects. It shifts the focus to cooperation. The students are no longer passive receivers but have to take responsibility and participate,” says Augestad.

Impressive Students

When Scientist Factory visited the Streetlight School, we struggled to see that the students lived in extremely challenging circumstances. We were greeted by a school full of happy children who played freely both indoors and outdoors, and we didn’t see a single instance of conflict. On the contrary, we could give 45 fourth graders measuring cups, water, and string without any difficulties. The students explored how they could move water from one cup to another using the string and measuring cup. The students were very knowledgeable and full of curiosity when we discussed the experiment afterward.

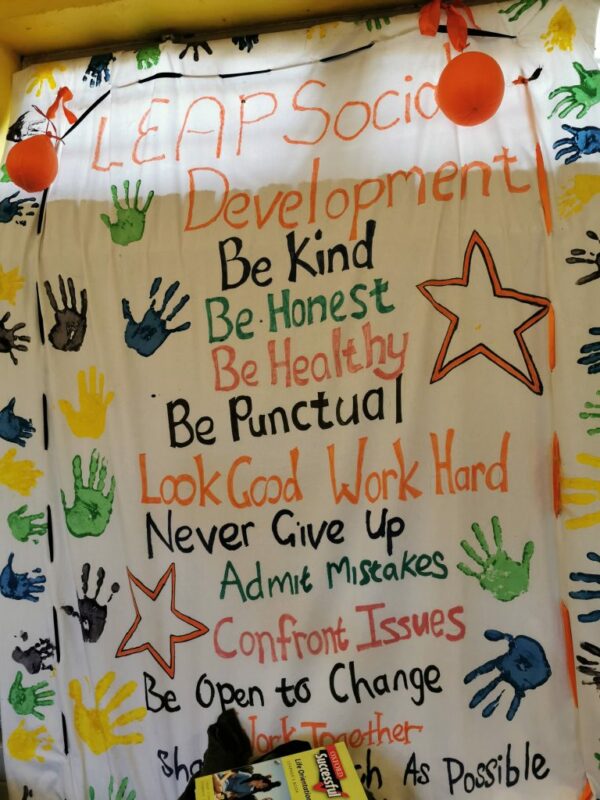

Leap schools

We also visited the LEAP School on this trip. Located in a township in Cape Town, the teachers largely relied on traditional methods. What’s special about this school is the environment which is characterized by deeply engaged teachers and a school culture that prioritizes the well-being of all students.

Many of the youths have had traumatic experiences. For this reason, conversational groups meet every day where the students share their thoughts and feelings with each other under the guidance of an adult. The results are astonishing. Despite a difficult upbringing, 96% of the students pass high school. The national average in South Africa is 74%.

The secret to good teaching

A few weeks later, I found myself in a dinner with education experts and told them about Streetlight and LEAP. Han Sølberg, professor of STEM-didactic at the University of Copenhagen, was there. He had some interesting observations about what I could share from my trip.

“I have begun to wonder if the effect of teaching is closely related to psychological treatment. It turns out that the most important element of therapy isn’t the method the therapist uses, but the therapeutic alliance between therapist and patient. Something similar might be true of pedagogical methods, that they are far less important than the relationship between teacher and student,” Sølberg says.

Research into pedagogical methods shows that few methods always have a good effect. If the student trusts the teacher, nearly all forms of teaching seem to work, even for students who struggle. A good teacher also creates a good class environment, something we know is decisive when it comes to learning. Schools have to promote learning across their entire organization. The teachers need to be engaged with the students, the classroom environment has to be supportive, and the teachers need to cooperate well amongst themselves, Sølberg says.

Sølberg’s reflections made me think about something Augestad told me about her work at Streetlight:

“Even though I didn’t compromise on what tools we were to use, I gave the teachers the time and support they needed to find their way. I observed all the teachers during the whole first year, and had individual meetings with all of them on a weekly basis about what challenges they faced and how they could be solved. Quality education isn’t rocket science, but it requires structured and nurturing work. The teachers had to think of the students as their own children and love them.

Scientist Factory’s journey to South Africa was sponsored by the Kavli Foundation.